Please tell us a little bit about yourself.

I grew up in Richmond Hill, Ontario, where the community was really active with sports. Our next-door neighbours were a family of four boys who were all sports enthusiasts, and my parents were both also sports enthusiasts. So I think that being around a lot of people who were playing sports, and spending time outside in a fairly safe and active community made it natural that I would be curious about moving my body, and bonding with family and friends over sport, activities, movement, and competition.

When I was really young, I did horseback riding and gymnastics. Then through high school I was part of a good number of non-mainstream sports. I played field hockey, curling, badminton, and then in university, I did rowing. I have always been in love with long-distance running. I also loved a couple of sports that didn’t love me back as much. I am quite short, but I loved basketball and volleyball. The non-team sports that I enjoy are snowboarding and waterskiing.

In school, I found that I was really interested in science. So as a young kid who was interested in both sports and science, it seemed like a natural progression to think about how the body works, how to nourish my body to perform better when it comes to sport, and then the psychology of sport as well. Being an active person and being surrounded by sport, athletics and competition drove a lot of my interest into my career in medicine. Throughout high school, I stayed really involved in team sports and other extracurricular activities. I found that sports were a really good way for me to meet people who I wouldn’t have met in my classes or friend groups. Teams provided a great opportunity to connect with lots of different kinds of people, break down barriers and boundaries, and just exercise leadership in a totally different atmosphere than academics. I tried a lot of different sports when I was young, and that gave me the confidence to continue to try other things that were new. That confidence allowed me to venture to France on a student exchange, and to go to a University that was out of province where none of my friends went.

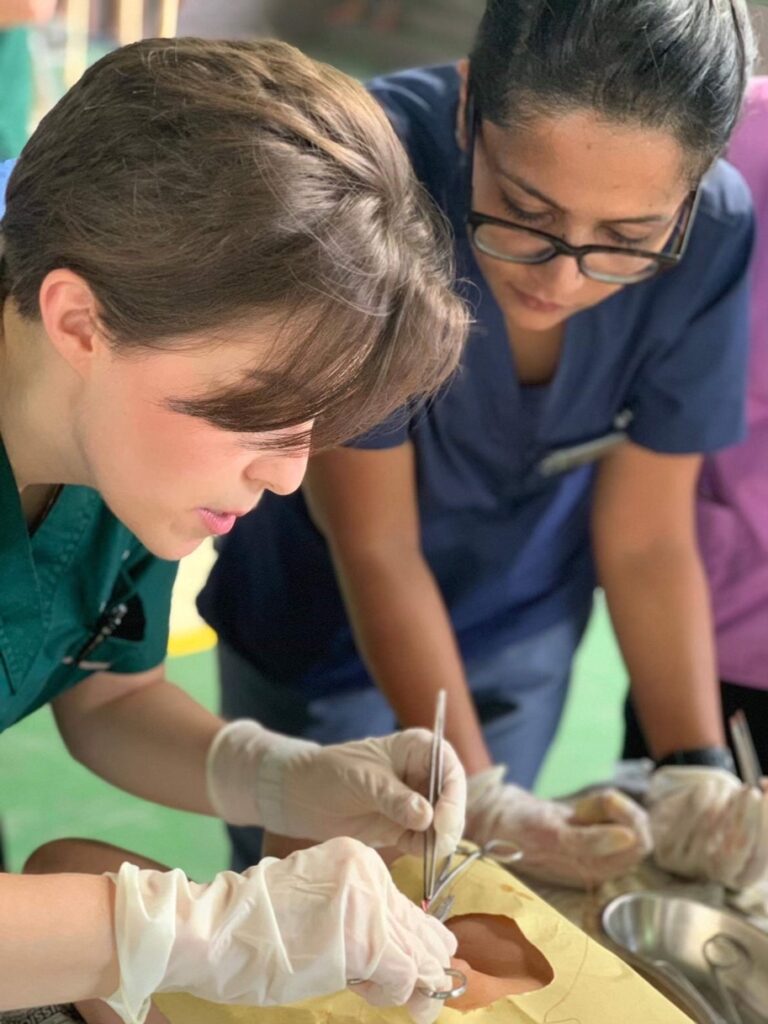

In University, I studied sciences, in keeping with my interest in the human body, then continued on with research, a master’s degree in public health, and then to medical school. I ended up studying medicine internationally and now I am doing my credentialing in Canada and the United States. When studying away, I encountered language and cultural barriers, and participating in and supporting sports was always a great way to build rapport and feel a sense of belonging in new groups of people and new environments.

What lessons did you learn in sport that can be applied to your daily leadership?

I didn’t realize that I was learning these lessons when I was young… I learned how valuable these were later. Only upon reflecting on them now can I see that I’ve adopted them into my leadership style. I learned that there are so many different styles of leadership. When you’re on a sports team, there is a range of different personalities, and people playing in different roles, and this is needed to get the best results. I think when people think about leadership, a lot of people have one archetype in mind, like the confident, outspoken, motivated, driven… the most recognizable voice in the room that people just look to. But what I learned through sport is that there are a lot of different ways to show leadership. Some people are very quiet leaders, and it’s through their consistency, empathy, and communication where they end up being a leader and setting an example for everybody else on their team. There are also leaders who show you how not to lead, and sometimes those are the loudest people who are hard on everybody. People respect them, but they’re not necessarily the type of leader that you yourself want to be. So I learned about a lot of different personality traits through people’s leadership styles and the way that they conducted themselves in sport. This allows me to be dynamic in my leadership style, and see that there’s time to be the leader, and there’s a time to be the follower, and that being “a follower” is sometimes a display of leadership. There’s a time to be the person who just puts their head down and does the hard work and leads by example. And then there’s the time to be the motivational type leader, and so on and so forth…

What habits did you develop in sport that helped you become successful in your career?

With sports, I was able to develop the skills of being organized, having time management, and consistently investing to see long term results – doing things repetitively day in and day out. In a country like Canada where academics are so highly prioritized, sports were always looked at as a side gig and not a priority. So if you wanted to prioritize athletics, you always had to be good and making sure that you fit it in with school. You often see that the kids who are the busiest with all these extracurriculars are also the ones who perform the best in school. I firmly believe that correlation is not a coincidence–its because those people know how to prioritize their time and they know when something is important to them that they always will find the time to get it done.

In studying medicine, there are a million opportunities for being humbled, rejected, and disappointed, so sport helped me to develop the habit of continuous effort even in the face of disappointment. That it’s OKAY to LOSE, because that failure is temporary. Even when you underperform, you have to be able to self-motivate and be consistent about anything you’re doing. Because there’s a lot of things that you are required to do with your day to day work, but it doesn’t always seem like you see immediate payoff. So being accustomed to the discipline of athletics allows you to develop the habit of discipline of doing things on a daily basis. And then seeing that slight progression on the daily which turns into massive results over time. You can replicate that into literally any anything you do.

I think the coolest and maybe strangest habit I developed in athletics and sport is self-talk. I didn’t even do this intentionally when I was a kid, I would just do it. And then through my studies when I started to become aware of psychology and neurobiology, I started to see that self-talk is actually a highly effective and well-studied phenomenon that people can use to get better results, develop confidence, and become more successful in their careers.

What advice do you have for parents, coaches, and or sport administrators to improve inclusion in sport?

We are fortunate that in the city of Toronto we have a very, very diverse population of people. So it’s very possible that you have access to try a lot of different sports. But based on what sports your parents played, or what sports are common or popular in your cultural background and your community, that’s what people just naturally end up gravitating toward. Public education affords a really good opportunity to expose everyone to a lot of different sports and activities. But I think it can also provide a great opportunity to learn about the lesser-known or lesser celebrated games (for example cricket) and the places in the world where cricket is popular, and the cultural understanding that goes along with that. Sports can serve as one of those entry points, similar to food, where it’s an opportunity to get to know a culture. When you enjoy a certain food, you want to learn more about where it came from, and the people there, and I think we can use this same framework for sports. Schools can introduce us to a sport or game, which isn’t well known in Canada, to improve inclusion.

There are also financial barriers to accessing sport. This limits inclusion, specifically in sports like hockey. It’s a celebrated sport in Canada, but it’s also one of the most expensive sports when it comes to rentals and equipment, and time.

Lastly, our Olympic athletes are well known to be some of the least financially supported athletes globally, and this limits inclusion for sure. Developing countries like the Philippines, where I lived for eight years, somehow find the means to do a lot more. In Asia, you see professional-level athletes being supported from age 12. If sport is presented at these very young ages as a financial opportunity for people, you would have more inclusion, and more diversity, especially for women.

5 words that best describe me are:

TENACIOUS | EMPATHETIC | DETERMINED | ADAPTABLE | ADVENTUROUS